A Case Study in Poor Capital Allocation: The Need for Greater Shareholder Protections

We examine the shareholder value implications of CBA’s acquisition of Colonial in 2000 as a case study in poor capital allocation.

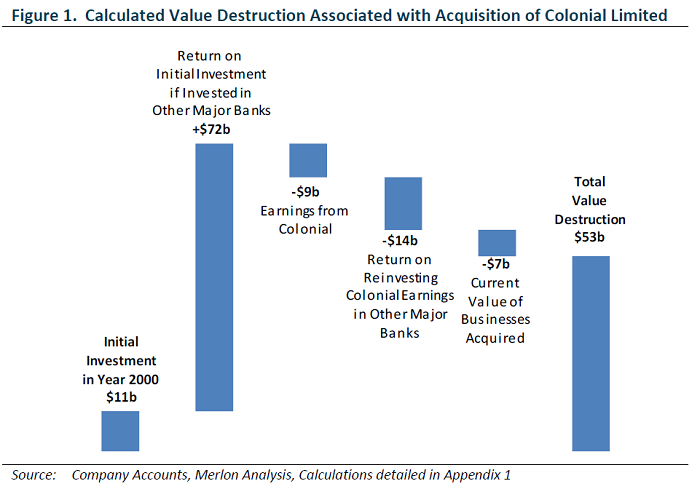

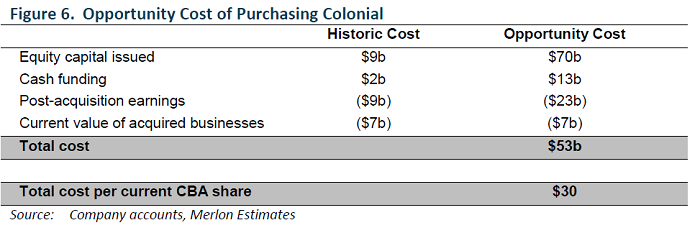

We calculate that the acquisition destroyed $53 billion in shareholder value relative to investing in the other major banks, equating to $30 per CBA share.

We believe the true value destruction was probably greater than our calculation given the low benchmark set by the other major banks; the opportunity cost of management focus diverted to the acquisition; and the brand damage incurred by managing the bank to meet short term financial targets.

Large transactions by large companies have broad ramifications against the backdrop of an increasingly passive approach to managing Australian equities and high Australian index concentration.

We advocate for stronger shareholder protections more aligned to the UK regime that requires shareholder approval for any deal exceeding asset, profit or value thresholds including 25% of acquirers market capitalisation.

Introduction

Poor capital allocation decisions are one of the most frustrating parts of being a patient and contrarian investor. We conduct detailed independent research and invest considerable resources and energy in developing a deep understanding of the value of the businesses we own. We focus on long-term fundamentals. We examine the underlying cash flows that businesses generate rather than the elaborately contrived measures of performance advertised by some management and boards. We do not subscribe to the “greater fool theory”.

Our approach allows us to patiently hold investments for long periods of time when many others are fearful, overly pessimistic, short term oriented and/or unwilling to deviate from popular opinion.

It is very disillusioning when all our efforts are tossed aside by boards and management teams that become fixated with chasing the latest growth opportunity or management fad through over-priced acquisitions or “simplifying the business” through inopportune and under-priced divestments.

Big companies, big bets, more stakeholders

When big companies make big bets, the issue of poor capital allocation impacts a much broader group of stakeholders. Millions of Australians hold equities through their superannuation funds and a large and increasing allocation of these funds are invested in proportion to index weights. When companies with large index weights underperform through incompetent management, retirement savings are depleted and government funded pension costs rise.

The two largest companies listed on the ASX are BHP Group Limited (BHP) and Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). Combined these two businesses make up 15% of the ASX200 index. Decisions made by the management and boards of these two companies have arguably been more influential in shaping retirement outcomes for millions of Australians than any other organisations.

In 2017 BHP’s capital allocation track record was called into question with claims the company had wasted $40 billion of capital. In this paper we examine CBA’s capital allocation track record. We calculate that the single decision in March 2000 to purchase Colonial Limited under the leadership of CEO David Murray ended up costing CBA shareholders $53 billion in today’s dollars. Taking into account qualitative factors, the true cost was probably much higher than this. Even at $53 billion, this cost is equivalent in size to REST Industry Super writing all of its investments down to zero, an event that would no-doubt prompt calls for a Royal Commission.

The Need for Change

What is remarkable against this backdrop is the lack of capacity for shareholders to voice concerns in relation to large acquisitions. Australia is unique in this regard. Last year we argued that shareholder rights should be better protected in relation to divestment decisions. In this article, using the Colonial acquisition as a case in point, we further argue that listing rules should be tightened to give shareholders a greater say in capital allocation decisions.

Many in the corporate community have suggested that shareholders elect directors to make decisions on their behalf and that overly cumbersome rules and regulations would make it difficult to get deals done. What is overlooked is where it impacts retirement savings the most – big companies making big bets – shareholders are more fragmented making it more difficult to hold boards to account. There are also instances – such as the recent AMP divestments – where unelected directors are making company shaping decisions with massive shareholder value implications.

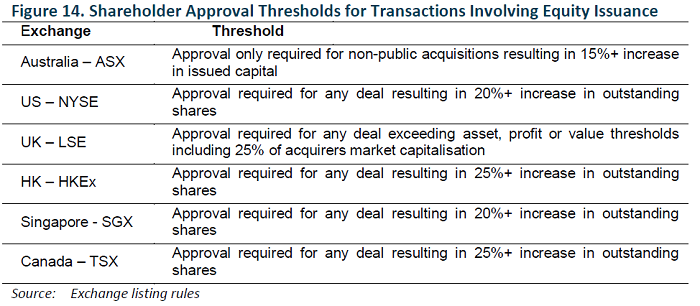

The ASX is an Outlier

The ASX listing rules are out of sync with equivalent rules in the UK, the US, Hong Kong, Canada and Singapore where stronger shareholder protections exist. We advocate strongly for a UK style regime that requires shareholder approval for any deal exceeding asset, profit or value thresholds including 25% of acquirers market capitalisation.

The Colonial Acquisition – Background Information

On 10 March 2000, under the leadership of CEO David Murray, CBA announced it had reached agreement to acquire Colonial Limited, a life insurance, funds management and banking group created through the amalgamation of 18 different businesses over the 5 years prior.

In consideration, CBA issued 351 million new Commonwealth Bank shares and paid $800 million in cash to Colonial income security holders. The equity issuance represented 39% of CBA’s pre-acquisition issued capital.

The strategic rationale for the acquisition was stated as follows:

- “The merger provides a strong platform for future international revenue growth.”

- “The merger will lead to enhanced revenue potential from opportunities to offer customers a wider product set, through a broader and more diverse distribution network.”

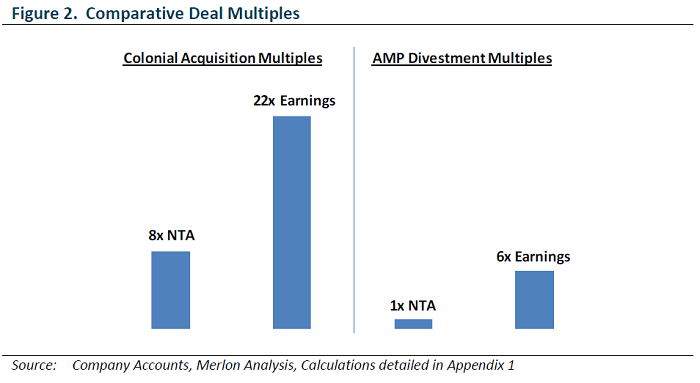

The deal had all the hallmarks of many “top-of-the-cycle” transactions with equity markets at all-time highs and asset managers trading at record multiples buoyed by the prospect of endless fund flow into compulsory superannuation.

Extreme Deal Multiples

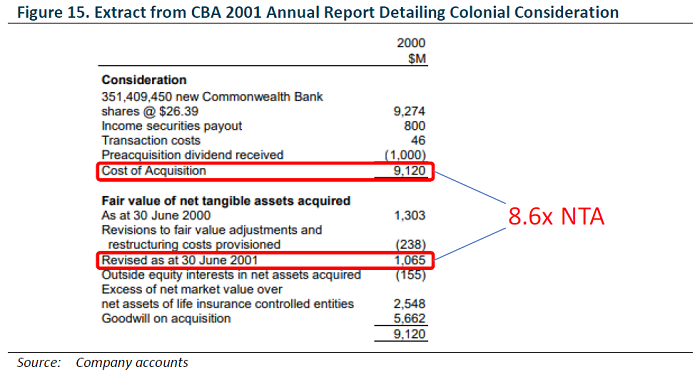

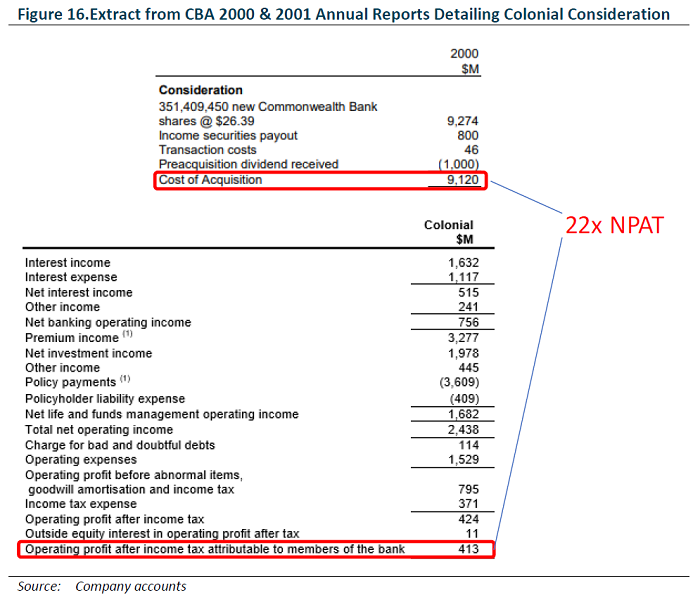

Based on its subsequent disclosures, CBA paid approximately 8x net tangible assets, 22x earnings and an even higher multiple of cash flow for Colonial. By comparison, AMP recently sold its life insurance operations for approximately 1x net tangible assets, 6x earnings and an even lower multiple of cash-flow.

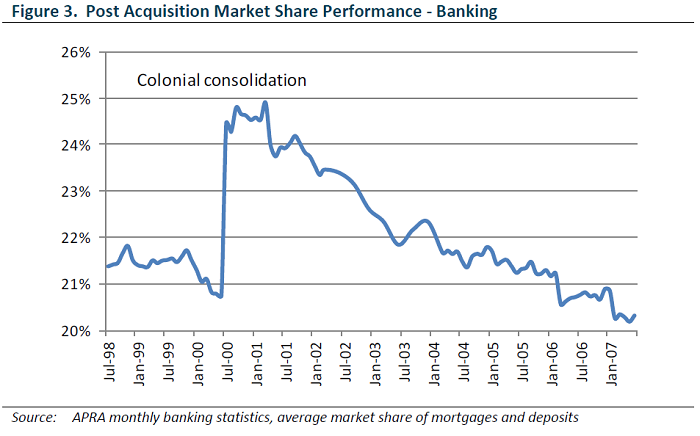

Post-acquisition Market Share Slide

Within five years of making the acquisition, CBA’s banking market share had reverted to pre-acquisition levels. While it is difficult to estimate what would have happened in the absence of the transaction, the implication is that there was little net benefit in the long run.

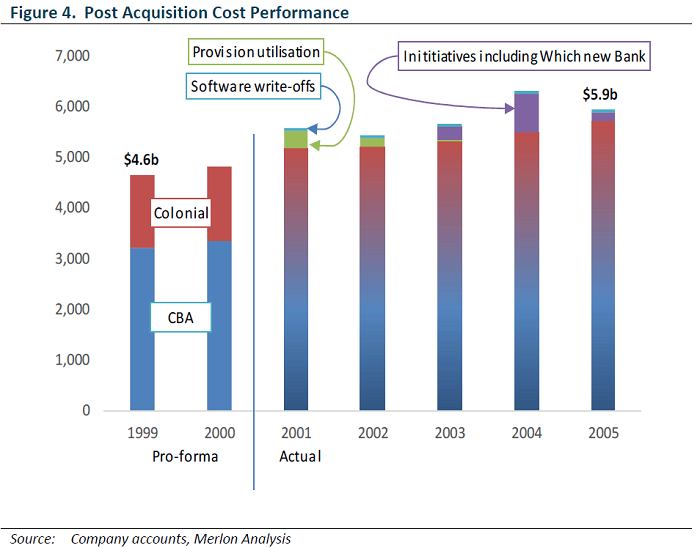

Elusive Synergies

With regard to synergies, like so many acquisitions, “advertised” cost savings merely served to offset cost growth elsewhere in the business. Prior to the acquisition, the combined cost base of Colonial and CBA was $4.6 billion (12 months to December 1999). Five years later, CBA reported consolidated operating expenses of $5.9 billion representing a compound annual growth rate of 5 percent over the period.

Cost growth was masked early in the period (as is often the case) by utilisation of restructuring provisions and the benefits of writing off capitalised costs. When the provisions ran out, CBA called a new round of “one-off” costs associated with the “Which New Bank” program.

Negative Market Reaction

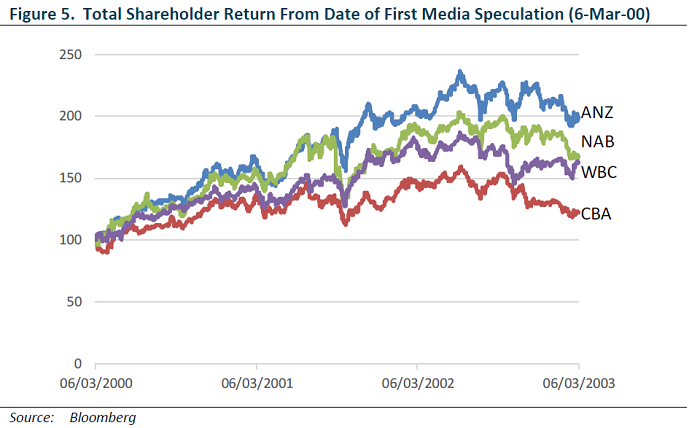

The Colonial acquisition was not well received, with the CBA share price underperforming 7% on the day of announcement. Of more significance, CBA underperformed its major bank peers by between 29% and 41% during the three years following the date of first media speculation.

Based on CBA’s market capitalisation of $23 billion on the day ahead of first media speculation, we estimate that shareholders would have collectively been between $11 billion and $19 billion better-off owning one of the other major banks over the subsequent three-year period.

Delusions of Grandeur

Despite the abysmal market share and cost performance, coupled with massive share price underperformance, CBA declared in its 2003 annual report:

“The expected synergy benefits of $450 million per annum, which were mostly banking related, were fully realised and in a shorter time frame than projected, making this a very satisfactory transaction for the Commonwealth Bank and its shareholders.”

Counting the Cost

The problem with simply looking at relative share price performance is that it does not consider how CBA shareholders would have fared in the absence of the Colonial transaction. It is possible, for example, that CBA would have outperformed the other major banks in the absence of the transaction which would imply a greater quantum of value destruction.

One way to deal with this issue is to assume that the transaction had never occurred. This would have meant:

- Equity capital that was issued to purchase Colonial could have been redeployed elsewhere;

- Cash funding that was used to purchase Colonial could have been redeployed elsewhere;

- CBA shareholders would have foregone earnings from the acquisition;

- CBA shareholders would have foregone the current value of the acquired businesses.

We deal with each of these aspects separately below. In summary, we calculate that the transaction ultimately cost CBA shareholders $53 billion.

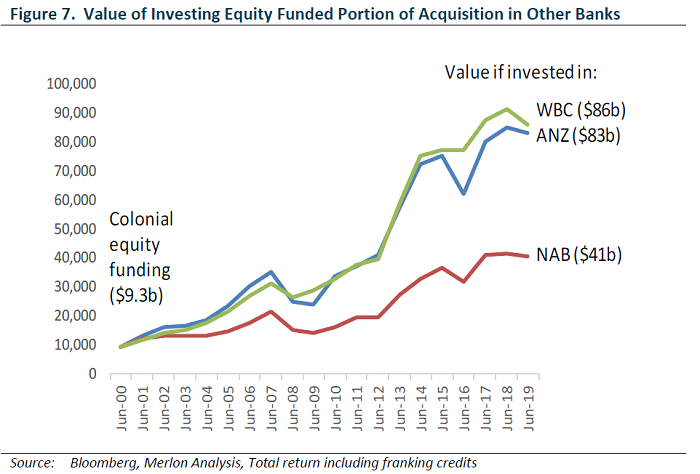

Equity capital issued to purchase Colonial

CBA issued 351 million new shares to acquire Colonial then valued at $9.3 billion. Had this $9.3 billion been invested in one of the other major banks we estimate that it would today be worth between $41 billion and $86 billion. If the amount had been deployed equally across the major banks the capital would today be valued at $70 billion.

Cash funding used to purchase Colonial

Our process assesses all potential investments on an unleveraged basis. In practice, our approach means we value surplus cash (or debt) on a dollar for dollar basis. In the case of financial companies, the concept of cash is replaced with the notion of surplus (or deficit) capital.

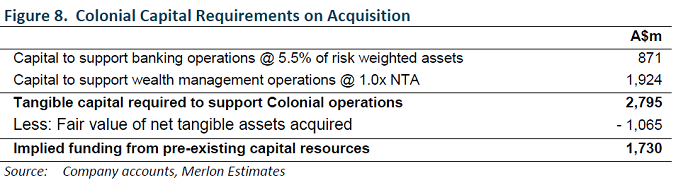

As detailed in Appendix 1, the fair value of net tangible assets acquired from Colonial shareholders was $1,065 million. This figure grossly understated the amount of capital required to support the Colonial businesses. It is remarkable that this issue was not identified during the course of due diligence and used as a means to break or renegotiate the initial merger agreement.

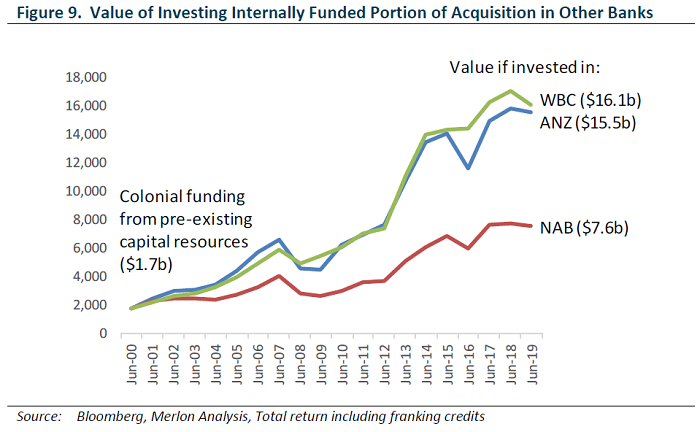

We estimate that the Colonial operations required approximately $2.8 billion of net tangible asset backing at the time of acquisition. This implies that approximately $1.7 billion in funding was contributed by existing CBA shareholders.

Had this $1.7 billion been returned to shareholders and reinvested in one of the other major banks (or reinvested in one of the other major banks by CBA) we estimate that it would today be worth between $8 billion and $16 billion. If the amount had been deployed equally across the major banks the capital would today be valued at $13 billion.

Earnings from the Acquisition

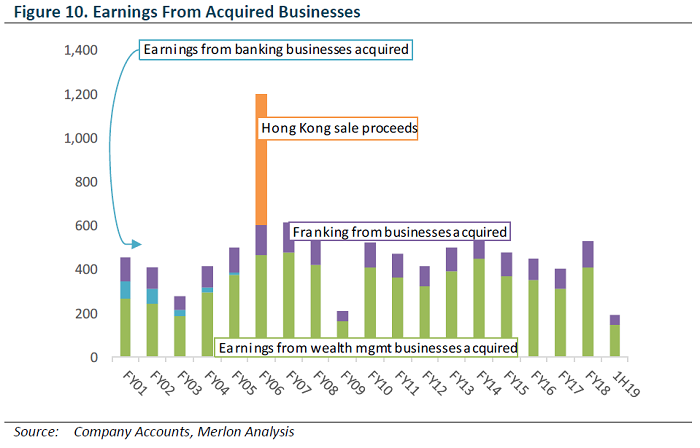

Offsetting the opportunity cost of the acquisition price outlined above, CBA has received earnings and franking credits from the businesses it acquired as well as sale proceeds from the businesses it has since sold. To estimate the amounts involved:

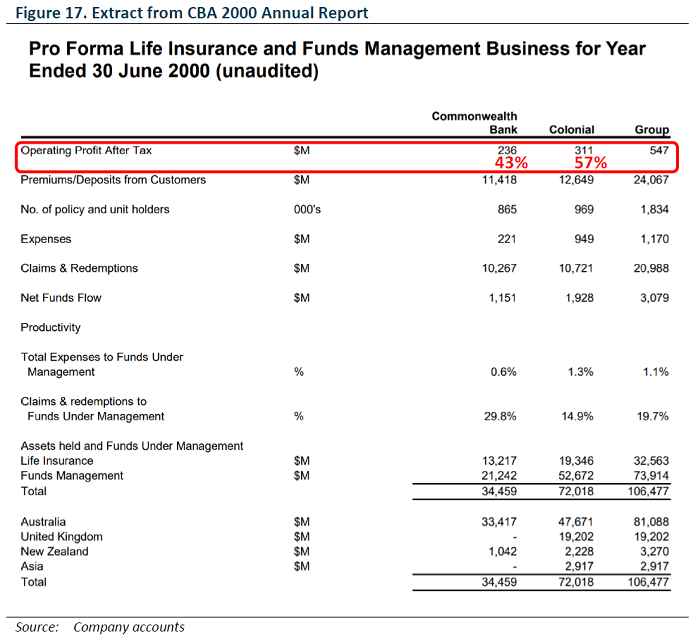

- We apportioned consolidated wealth management earnings based on the pro-forma contributions from CBA (43%) and Colonial (57%) as disclosed by CBA in its 2000 annual report (Appendix 2);

- We assumed that earnings from Colonial’s wealth management operations were 67% franked, proportionate to the segment contribution from Australia disclosed by the company in its results for the full year to December 1999;

- We assumed that bank earnings faded down to nothing over 5 years, proportionate to the decline in combined market share between 2000 and 2006 (refer Figure 3 earlier), even though costs would likely have been retained;

- We ignored synergies in light of the fact that CBA’s cost base grew at 5% per annum in the five years post acquisition; and

- We included the $0.6b proceeds from the sale of Colonial’s Hong Kong life insurance business as an additional offset.

In aggregate we calculate the earnings and sale proceeds received from the Colonial acquisition to be approximately $9 billion since the date of acquisition.

To be consistent with our analysis so far, this $9 billion figure significantly understates the true value of the earnings because the earnings improved CBA’s capacity to pay dividends and these dividends could have been reinvested by CBA shareholders elsewhere. For example, if the first-year (FY01) earnings contribution from Colonial of $455 million was reinvested into ANZ shares it would be worth $2.9 billion today.

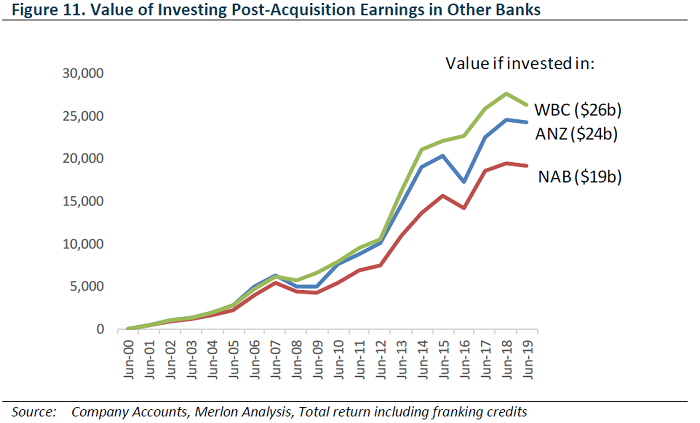

Had the $9 billion in earnings been reinvested in one of the other major banks over the years, we estimate that it would today be worth between $19 billion and $26 billion. If the amounts had been deployed equally across the major banks the capital would today be valued at $23 billion.

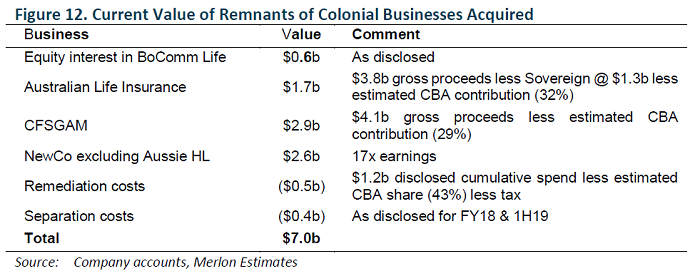

Current Value of Acquired Businesses

The remnants of the Colonial businesses acquired have all been earmarked for sale. Based on disclosed information we estimate these businesses will realise approximately $7 billion in net proceeds.

Unquantifiable Costs

While we have attempted to quantify the financial cost of the acquisition, it is truly impossible to know how CBA would have performed in the absence of the transaction. In particular:

- The management energy on integrating the businesses could have been diverted elsewhere;

- In many respects the “major bank benchmark” was an easy hurdle given each bank had its fair share of poor capital allocation decisions (WBC – SGB acquisition; NAB – MLC & Homeside acquisitions, as well as rapid UK expansion at top of cycle; ANZ – ING acquisition, foray into Asia) and,

- The focus on delivering on financial targets associated with the acquisition could have led to short term decision making.

In reality, we think CBA could have massively outperformed its peers in the absence of the acquisition and that the $54 billion cost estimate materially understates the true opportunity cost of the deal.

Unsustainable Customer Outcomes

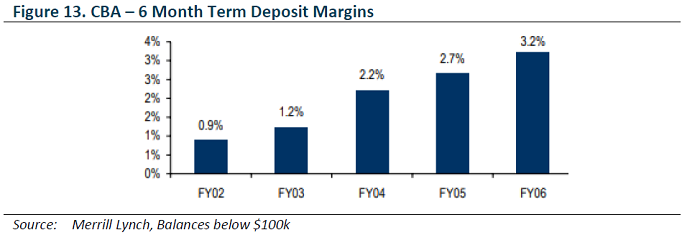

Regarding its focus on delivering short term financial targets, we note a concerted effort by CBA to increase earnings through pricing its term deposits uncompetitively through the period post-acquisition period.

The Australian newspaper quoted an internal email from ASIC in an article dated 29 March referring to this issue reportedly stating:

“ASIC concluded from the investigation that CBA consciously devised and implemented a strategy that … utilised the ambiguity (at minimum) of its PDS and renewal notices” and “utilised its extensive knowledge of a particular class of depositors who were price inelastic … to lower non-headline rates to levels which were at times below inflation and ensuring that customers automatically rollover into non-headline rates to obtain hugely inflated profits from the price inelastic deposit holders.”

This matter was raised in Merrill Lynch research published on 25 March 2005 that stated:

“Since mid-2002, CBA has uncompetitively priced for profits across its cash management account (“CMA”) and sub-$100k term deposit product ranges … We do not believe that CBA’s strategy is sustainable over the medium term, which presents earnings risk (circa $250m) should the bank re-price to peer levels.”

We also note that CBA persistently ranked the worst of the major banks on measures of customer satisfaction during the integration period.

The Merlon Investment Process & Capital Allocation Risk

Over the years we have unfortunately seen many boards allocate capital poorly. These decisions are most damaging when transactions are large relative to the size of the company concerned and / or where equity is issued to fund the transactions at depressed prices.

Assessing the Risks

As part of our qualitative review process we score companies on a variety of measures relating to Industry Structure (score out of 15); Competitive Advantage (score out of 9); and Governance and Management (score out of 11). The latter category is decomposed into Governance (score out of 5); Capital Allocation (score out of 3); and Execution (score out 3). We do not screen on quality but seek to ensure our estimates of sustainable free cash flow for companies appropriately reflect qualitative characteristics. These estimates of sustainable free cash flow, in-turn, drive our assessments of fundamental value.

In determining our management scores, we engage with boards and management; consider the track records of the companies and individuals concerned; review board composition for diversity and appropriate balance of power; examine remuneration models/equity alignment; and, seek to understand companies’ strategies to generate acceptable and sustainable returns. All our scores are subject to rigorous peer review.

Valuation

To the extent that our assessment of Governance and Management can be built into our assessment of sustainable cash flow we will attempt to do so. This is easier for companies with a track record of making regular acquisitions or investments where we can measure historical return outcomes and build a “budget” or “buffer” into our assessment of sustainable free cash flow.

From a Merlon perspective, we are always highly sceptical about acquisition synergies, particularly when coupled with dubious accounting practices and resultant margins that are out of sync with local or international peers.

Conviction

Alongside valuation, we assign a Conviction Score to each stock we cover reflecting the degree to which we think there is misperception in the market. Our Conviction scores and our assessments of relative fundamental value determine our ultimate portfolio weights.

This important element of the process reflects whether our view on capital allocation risk is more or less pessimistic than the market. We start by factoring the risk of a capital misallocation into our bear case valuation scenarios but may also revise down our base case valuations if we think a poor decision is “more likely than not”. This allows us to determine what level of capital allocation risk the market is already pricing into the stock. For example, if the share price is already trading close to our bear case scenario, we may conclude the market is equally or more pessimistic on management than us, leading to a positive conviction bias. Alternatively, if the share price is trading well above our base case valuation, but we still consider capital allocation risk to be a key issue, this may lead us to have a negative conviction bias.

Managing Positions Post the Event

Often – as was the case with the Colonial acquisitions – poor decisions take many years to be reflected in market expectations. In these instances, if we own such companies – we may be presented with the opportunity to exit our positions. This was the case recently when Clydesdale Bank purchased Virgin Money in the UK.

At other times, these decisions are capitalised more immediately into market expectations – as was the case with the recent AMP divestments. In these instances, it is not always in our clients’ interests to exit positions at fire sale prices.

The Need for Greater Shareholder Protections

Last year we wrote about Divestments and Shareholder Rights noting that generally boards have taken a conservative approach to seeking shareholder approval in relation to divestment decisions. That said, we do think the recent AMP divestments highlighted the need for tighter ASX listing rules regarding the quantum of a firm’s operations that can be divested without shareholder approval.

As the Colonial case demonstrates, the impact of large acquisitions can also be devastating and long-lasting for shareholders. To compound the issue, shareholders rarely have a say in the matter. Unlike many other major exchanges, and contrary to rules in relation to divestments (if implemented properly), the ASX allows boards to deploy large amounts of capital without shareholder approval.

Overseas Benchmarks

In the US, for example, companies listed on the NYSE must obtain shareholder approval for transactions that will increase the buyers shares by more than 20%. This is not perfect, because a cash transaction requires no approval, but would be a step in the right direction and might have prevented the Colonial scenario.

In the UK, listing rules go one step further by requiring shareholder approval for any transaction exceeding asset, profit or value thresholds.

The Role of Superannuation & Index Investing

There are strong arguments, in our view, that shareholder protections in Australia should be tighter. The advent of compulsory superannuation and growing adoption of a passive investing approach to managing Australian equities are important considerations.

It has been well documented that many Australians are not actively engaged in managing their superannuation investments. Through passive investment strategies it could also be argued that many large superannuation funds are not as actively engaged in the management of individual company investments than has historically been the case.

This shift in the market structure has placed a much greater onus on company boards to act benevolently in the best interests of their shareholders. Much has been said about underperforming superannuation funds, but underperforming boards and management teams can be equally destructive to long term public finances, particularly where such companies are as large as the Commonwealth Bank.

Concluding Remarks

In investing it is instructive to examine mistakes and study the past. An overarching observation – made by Warren Buffet among others – is that one of the most important things that a CEO does is allocate capital, yet few CEOs are trained for capital allocation because they rose through other streams in the business. Boards need to understand this and play an appropriate gatekeeping role. Yet there are not many large company directors with capital allocation expertise.

Tightening shareholder approval thresholds would be a great step forward in improving board accountability and driving better capital allocation outcomes for all shareholders – passive and active. This might well prevent the massive and long-lasting value destruction shareholders experienced with the Colonial transaction from repeating itself.

Author: Hamish Carlisle, Portfolio Manager/Analyst

Appendix 1: Calculation of Transaction Multiples

Appendix 2: Contribution to Wealth Management Earnings

Disclaimer

Any information contained in this publication is current as at the date of this report unless otherwise specified and is provided by Fidante Partners Ltd ABN 94 002 835 592 AFSL 234 668 (Fidante), the issuer of the Merlon Australian Share Income Fund ARSN 090 578 171 (Fund). Merlon Capital Partners Pty Ltd ABN 94 140 833 683, AFSL 343 753 is the Investment Manager for the Fund. Any information contained in this publication should be regarded as general information only and not financial advice. This publication has been prepared without taking account of any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Because of that, each person should, before acting on any such information, consider its appropriateness, having regard to their objectives, financial situation and needs. Each person should obtain a Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) relating to the product and consider the PDS before making any decision about the product. A copy of the PDS can be obtained from your financial planner, our Investor Services team on 133 566, or on our website: www.fidante.com.au. The information contained in this fact sheet is given in good faith and has been derived from sources believed to be accurate as at the date of issue. While all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the information contained in this publication is complete and accurate, to the maximum extent permitted by law, neither Fidante nor the Investment Manager accepts any responsibility or liability for the accuracy or completeness of the information.